Escaping poverty is no mean feat, but having to do it twice makes the journey even more arduous. This is the precarity most nations face as they enter the middle-income level and become stuck in what is known as the Middle-Income Trap (MIT). They get trapped in a difficult place between low-wage, low-income countries with competitive exports in mature industries and high-income countries that dominate technologically evolving industries. It is necessary to explore whether India can avoid being caught in these deadly jaws and what needs to be done to circumvent this trap.

How to circumvent an MIT

Three significant factors are listed in Krishnamurthy Subramanian’s book “India@100” to explain the vulnerability to an MIT – i) a slowdown of sectors that fueled the transition from low- to middle-income, ii) an excessive reliance on industrial policies at the cost of technological advancement and innovation, and iii) stagnant institutions incapable of catering to complex economies. The World Development Report also highlights the need for strong institutions, the lack of which can be debilitating for the economy due to significant structural imbalances. It delves into deep discussion, with an overarching theme: the need to incorporate two key transitions—from 1i to 2i and from 2i to 3i.

Initially, investment needs to be combined with infusion (2i), i.e., technology transfer and imitation of best practices, to maximize the productivity of the investment, leading to an increase in income.

The second transition involves adding innovation to the mix (3i), i.e., when the marginal productivity of infusing foreign technologies is almost depleted, governments can incentivize domestic innovation. This process needs to be supported by a solid institutional framework; otherwise, it might result in missed opportunities. For instance, Brazil bypassed the infusion stage and directly incentivized innovation through subsidies funded by taxes on international intellectual property. This resulted in low-quality innovations with limited international relevance and lower productivity and wages for skilled workers.

Is India trapped?

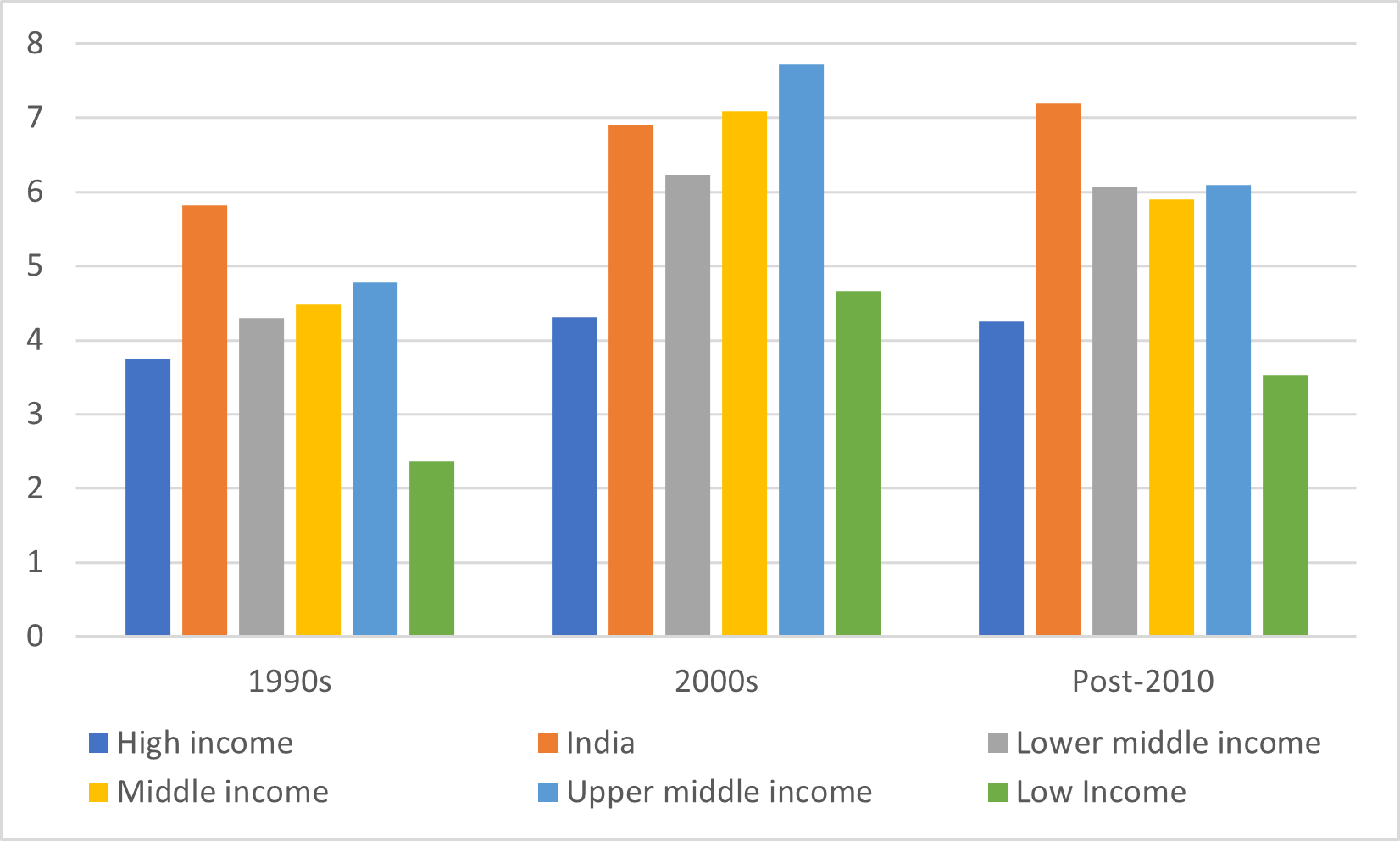

India is one of the fastest-growing large economies, projected to grow at 7 percent in the current fiscal year and projected to settle at 6.5 percent. This is more than twice the projected global growth rate and almost four times that of advanced economies. As shown in Figure 1, India has grown faster than both low- and high-income countries since the 1990s, with the only exception being the 2000-09 period, when its growth fell a little short of the advanced economies. Both forecasts and historical trends showcase that India is not yet caught in an MIT, with no indication of such a hindrance in the near future.

Figure 1: Average decadal growth rates

Source: World Bank (computed by author)

The World Bank classifies any country with Gross National Income (GNI) per capita (Atlas method) between $1,146 and $14,005 as a middle-income country. As of 2023, India’s GNI per capita was $2,540. Thus, an almost sixfold growth is required to position India as a high-income country and to make it a Viksit Bharat. However, countries are expected to encounter the MIT at a later stage of this transition, rendering India’s possibility of getting trapped uncertain for now. Considering a growth rate of around 8 percent, India will have a per capita GDP of around $16,100 in 2047. Given this trajectory, India may face the risk of an MIT in another 18 years, or around 2042.

However, the likelihood of such an occurrence is minimal, given that the country has been on a growth trajectory of 8 percent for almost 2 decades. An MIT is possible only if the institutions and policies go awry during the transition. The fundamentals of economic growth must be solidified to ensure the growth process is sustainable. These include macroeconomic stabilization, strong institutions and the rule of law, human capital development, and access to open and competitive markets. Usually, growth slowdowns are primarily productivity slowdowns. Thus, government expenditure on education, healthcare, and technology needs to be amped up to sustain the total factor productivity growth that has ensued in the last decade. This, in turn, will attract private investment. With the appropriate institutional framework in place, this can catalyze the transition to 2i and 3i.

India’s Trump Card

India’s growth on the supply side has been primarily led by the services sector, which contributed almost 64 percent to the country’s Gross Value Added (GVA) in 2023-24. Unlike the East Asian Tigers or Latin American countries, India circumvented the transition from agriculture to industry and directly embarked on a services-oriented growth trajectory. This was fueled by the 1990s economic reforms and the Information and Communication Technology (ICT) revolution. Leveraging its comparative advantage in medium- to high-skilled labor, India seized a 4.6 percent share of global services exports. This imposed costs on the country’s industrial sector.

India’s ace in the hole is its untapped manufacturing potential. It is a sector that can significantly develop with the appropriate policy structure and has been heavily prioritized with incentive schemes in the last decade. The goal of Aatmanirbhar Bharat, i.e., making competitive manufactured goods in India, integrating Indian businesses into the global value chain, and specialized exports, can provide massive momentum to industry and bolster growth. Schumpeterian creative destruction, a process where outdated sectors make way for more innovative and efficient ones, is inevitable and pivotal to this transformation. Incentivizing incumbents and welcoming new entrants with a maturing demographic dividend will provide large economies of scale. Instead of only focusing on the 2i to 3i transition, India can harness an unprecedented structural transformation where industry dominates in a service-oriented economy. The transition to Viksit Bharat will require continual targeted policy intervention and undeterred expansion of free markets.

The views and opinions expressed here belong solely to the author and do not reflect the views of BlueKraft Digital Foundation.